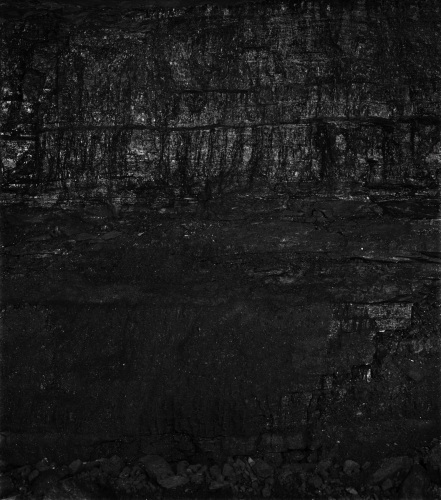

Miles Coolidge, Coal Seam, Bergwerk Prosper-Haniel #3, 2013, pigment inkjet print, 57 x 50 inches (145 x 127 cm)

It is contemporary photography roundup time in New York, with major exhibitions appearing concurrently at the Museum of Modern Art (“Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015”) and the Guggenheim (“Photo-Poetics: An Anthology”). The Met’s contribution, “Reconstructions: Recent Photographs and Video From the Met Collection,” is not framed as a showcase of what’s new, hot or trending, but it relates both subtly and significantly to these two exhibitions. The show includes 18 works by 15 artists acquired during the past seven years – work that Met curators think will endure historically.

While there are no overlaps with the artists in the MoMA and Guggenheim shows, the correspondences between those exhibitions and “Reconstructions” are telling. Moyra Davey, whose practice combines writing and photography and feels like a template for the Guggenheim’s formally rigorous “Photo-Poetics,” is included in that show as well as the one at the Met. Her work “Kevin Ayers” (2013) consists of photographs of record store patrons and vinyl record bins, printed on fold- up mailers addressed to a curator at the Tate Liverpool, which commissioned this work, and arranged as a grid on the wall. The work pays homage both to a founding member of the ’60s English psychedelic rock band Soft Machine – Mr. Ayers, who died in 2013 – but also the end of an era of vinyl records and its counterpart in the photography world, the death of so-called analog chemical photography.

Erica Baum, who is also included in “Photo-Poetics,” looks back to the analog world of paper books, using them as raw material and photographic subjects. Ms. Baum is represented here by four photographs of books from the “Dog’s Ear” series, with pages folded down such that new texts and meanings are generated by the images.

If “Reconstructions” overlaps in places with the solemn, serious “Photo-Poetics,” it also channels some of the brash, mass-media-savvy of MoMA’s “Ocean of Images,” too. Lucas Blalock, who has several works in that show, is represented at the Met with a chromogenic print, “Both Chairs in C W’s Living Room” (2012), which has also been used to publicize the Met show. An example of post-Internet artists who demonstrate a simultaneous respect and irreverence for digitalmedia and editing tools, “Both Chairs” looks like a cross between a classical still life and an upscale home-furnishings advertisement. It contains perverse passages in which the artist has digitally “corrected” the floor, chair and curtains to create visual jokes reminiscent of how Cubists hijacked painting’s system of illusionism a century ago.

What the Met can add powerfully to any conversation on photography is a sense of its deep history – that is, how new styles and techniques are often rooted in forgotten or submerged traditions. (This is also played out in the installation, through Jan. 18, called “Grand Illusions: Staged Photography From the Met Collection,” which uses both 19th-century and contemporary photography to make its claims.) Within “Reconstructions,” several works draw from and mimic early photography. Thomas Bangsted’s black-and-white photograph, “Last of the Dreadnoughts” (2011-2012), features an American warship that was once painted with “dazzle” camouflage, which was invented by a Vorticist painter to confuse German optical range-finding devices. Mr. Bangsted’s digital manipulations – including the ship’s dazzle effect and reflections in the water – partially recalls Gustave Le Gray’s 19th-century photographs, which used different negatives to achieve the desired effect of placid sea and expressively cloudy sky.

Miles Coolidge’s dark, nearly monochrome image from inside a German coal mine – made with an inkjet printer that uses coal products – harks back to photographers like Aaron Siskind, who approximated the painterly abstraction of his midcentury peers. But it also pays sly homage to the German conceptualists Bernd and Hilla Becher, Mr. Coolidge’s professors at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie, who documented the industrial machinery that brought the coal to the surface of this very mine. Meanwhile, Shannon Bool’s black-and-white silver gelatin print “Nadja” (2014) looks like an example of African photography but is actually a collage made from culturally disparate sources: a Surrealist-era mannequin from the 1925 Decorative Arts Exposition in Paris and a tribal motif on a ceremonial house from Papua New Guinea.

There is another narrative quietly threading its way through “Reconstructions.” This is the enduring influence of the Pictures Generation from the ’70s and ’80s, which helped put photography at the center of contemporary art. Doug Eklund, the Met curator who organized this show, also organized the benchmark exhibition “The Pictures Generation, 1974-1984” at the Met in 2009. That show examined the first generation of artists to grow up with television and subsequently appropriate mass-media images for their work, undermining modernist claims to originality.

Clegg & Guttman’s “Our Production, The Production of Others: CD Cover Version II” (1986-2012), a portrait of a German classical music group that was used for one of its album covers, is emblematic of this lineage in which the image is a simulacra: a copy with no original; an artwork put into commercial, promotional use. Similarly, Roe Ethridge’s “Double Ramen” (2013) is a perfectly deadpan, post-Pictures diptych juxtaposing two close-up photographs of uncooked ramen noodles.

But the most telling image in the exhibition is a photograph by Sarah Charlesworth, a leading member of the Pictures generation, which included many women (among them Cindy Sherman, Louise Lawler and Sherrie Levine) who “used” photography for art-making rather than for identifying themselves as photographers per se. Ms. Charlesworth’s chromogenic print “Carnival Ball” (2011) does not derive from, or comment on, mass-media imagery. Instead, using only the light available in her studio, she photographed a crystal ball against a striped background to achieve what looks like a magical effect. The photograph hints at advertising displays and the “magic” of special-effects photos, creating a nice link to a younger generation of artists that consciously celebrates the “magic” (rather than the “culturally constructed” nature) of photographic imaging.

Ms. Charlesworth serves as a kind of patron saint at the Guggenheim: the frontispiece of the catalog for “Photo-Poetics” includes a dedication: “In memory of the life and work of Sarah Charlesworth,” who died of an aneurysm in 2013.

Museums are a challenging place to test out contemporary theories of art history, which, after all, is the product of consensus: groups of artists, critics and historians agreeing, even provisionally, on who and what is important at a given moment. While the Guggenheim and MoMA offer largely divergent narratives of the current era, leaning toward the Internet’s circulation and dissemination of images and the rigorous legacy of conceptualism, respectively, “Reconstructions” functions like a gentle mediator, offering a perspective rooted in the long history of photography that already exists within the museum itself.

“Reconstructions: Recent Photographs and Video From the Met Collection” is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through March 13; 212-535-7710, metmuseum-.org.