John Zurier: On the Back of a Mirror

By Raphy Sarkissian

October 4, 2023

spring, that people

do not notice—plum blossoms

on the back of a mirror

—Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694)

On the Back of the Mirror—the title of this exhibition and also a painting—is as much an aura as anything else. A scent of spring. Old wood, dust, rain, scattered leaves, wet grass, stones.

—John Zurier

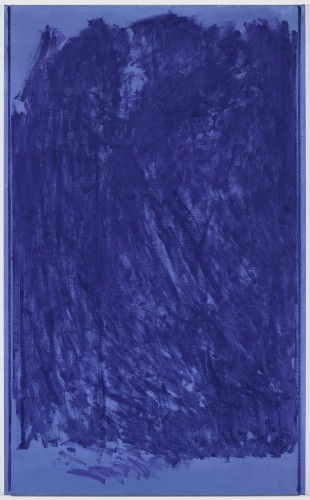

Tranquility and reflective expansiveness pervade the walls of Peter Blum Gallery, where the diaphanous colors of John Zurier frequently haze the distinctions between the concrete and ineffable, between opacity and luminosity, between tangible matter and color. On the Back of a Mirror comprises six medium-scale and nine large-scale paintings realized with the artist’s consideration of the distinct atmospheric conditions of Berkeley, California, and Reykjavík, Iceland. Though abstract, the paintings of Zurier emanate sensations of luminosity and spatiality. For Zurier, mark-making is not an end in itself, but a means of arousing phenomenological experiences and heightening consciousness. As Zurier has said, “I am interested in the gap between abstraction and evocation, between what is determinate and indeterminate, direct and suggested. I hope the paintings can be seen as both austere and poetic.”

Greeting the visitor with a sense of asceticism and a restrained syntax, Kōyasan (2022), a pictorial investigation and an evident homage to Mount Kōya in Japan, offers itself as a visual haiku of a landscape. Dispersed upon a grayish ground, staccato brushstrokes in teal green resonate as disseminating foliage set above a horizontal line segment bound to codify terra firma. As if it were a pictorial synopsis, Kōyasan encapsulates the formal essence of Zurier’s visual lexicon. Generality and specificity of titles, autonomy and referentiality, self-containment and context, form and content, line and color, figure and ground, surface and space: such are the fundamental dialectical elements that Zurier unceasingly permutates and reciprocates, re-presents and contravenes, discreetly inviting the observer to a plethora of signs, signifiers, references, and obtuse meanings.

With intoxicating shades of lapis lazuli, Egyptian blue, and ultramarine hovering atop such colors as sea green and emerald, After Carl Fredrik Hill II (2020–22) brings to mind, for instance, the Swedish painter’s magnificent Route de Paris II (1877) at Thielska Galleriet in Stockholm. Glimmer (2023), suggestive of an intriguingly absorbing tree allé embodied through shades of medium and light blue atop a yellow underlayer, evokes Cézanne’s Avenue at Chantilly (1888) of the National Gallery in London. If Cézanne’s practice were derived from the primordial observation of nature, along with the aesthetic elements and stylistic devices of Courbet, Delacroix, Chardin, and Poussin, it would be merely tenable to approach the evocative abstractions of Zurier as a continuation of that task. Except now the landscape of twentieth-century abstraction, overshadowed by the linearity of Mondrian and painterliness of de Kooning, has come to concurrently distill and ramify Zurier’s undertakings. “When I first saw a Cézanne painting up close,” explains Zurier, “I understood how the color is moving over the empty unpainted spots. It’s something that I still look at a lot, this aerated surface, the use of unpainted areas, ‘unfinished’ areas.”

White smudges of oil paint, traversing vertically upon the composition’s central axis, articulate the pictorial field of Langspil (Echo) (2023). The painting is an enthralling summation of indexical brushstrokes where colors interact restlessly before our eyes. Referring to a musical instrument and a painting, Zurier explains that “langspil” is an Icelandic three-stringed instrument that produces a humming sound when played with a bow. In turn, the “echo” within the title is a reference to Ferdinand Hodler’s painting Eiger, Mönch and Jungfrau in Moonlight (1908). By pairing Hodler’s symbolist representation of the three majestic mountains of the Swiss Alps and Icelandic music, Zurier invites the observer to reflect on the junctions of the visual and aural.

Bands of color intervene Zurier’s monochromatic coloration in such captivating oil-on-linen works as Attachment, Sketch for Winter II, Willow, and Tarn, all executed in 2023. Within the sensuality of these paintings, abstraction transpires as an intimation of nature, where evocations of old wood, dust, rain, scattered leaves, wet grass, and stones recall Cézanne’s claim that shape, tactile properties, resonance, and odor establish a given color in a painting.

In Siglufjörður, with its title referring to a town in a narrow fjord in the northern coast of Iceland, Zurier has intercalated three horizontal line segments in dark glue-size tempera upon a washed field of grays, greenish blues, bluish greens, and celadons. The linen here, attentively mounted on board with nails, partakes in the pictorial discourse, recalling Magritte’s strategy in doubling and defying illusionism through the depiction of nails on the edge of the painting held on an easel in The Human Condition (1933). Zurier, having dispensed with the entirety of Magritte’s pictorial content, replaces illusion through a painting’s optical and haptic properties. For Zurier, abstraction is a poetic and phenomenological means of accessing the primordial.