Paul Fägerskiöld: 2100

By Jess Chen

March 12, 2022

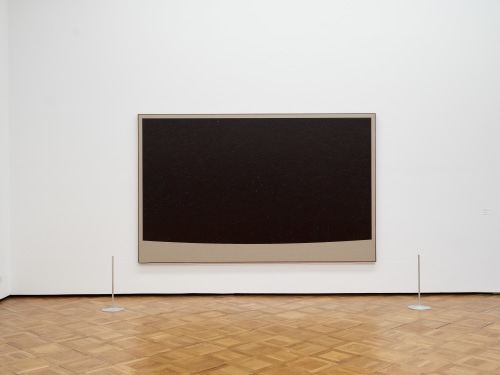

Astronomy and astrology were once one, a single discipline that studied and interpreted celestial phenomena. This link between the stars and human fortune, the calculable orbit of planets and the uncertainty below, is the central dynamic in Paul Fägerskiöld’s exhibition 2100 at Galerie Nordenhake’s Berlin location. If the fault is not in our stars, what might we find by looking at them? Fägerskiöld suggests a possible answer in 2100, which positions stargazing outside human-centered modes of introspection. The show features seven oil paintings of the night sky in Rome, Berlin, Kaliningrad, Mount Everest, and other locations in the year 2100, based on projections modeled by the aptly named software Starry Night. Though the paintings are of different sizes, each work follows the same pattern: a depiction of the sky—small white dots on solid-color ground, shaped like a rectangle on three sides with a catenary-curved bottom—and a border of unpainted linen. Equally, if not more important is what the paintings do not depict. Fägerskiöld omits anything animate or produced by a living being, dissolving any semblance of a relationship between foreground and background. His work is a window into the endless expanse of sky, where change occurs on a scale and magnitude unperceivable by the human eye. In essence, Fägerskiöld works from the viewpoint of deep time.

2100 is not Fägerskiöld’s first experiment with the concept. Last year, his exhibition Blue Marble at Kunstmuseum Thunn included paintings of the night sky in Stockholm in the year 100,000, as well as in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in 1889 (van Gogh’s view while painting Starry Night). The year 2100, however, is less abstract to the viewer—only a few generations into the future. 2100 is also the upper limit for most climate projections, owing to the unpredictability of climate policy. In the best-case scenario, the earth will warm significantly, coastal areas will be submerged underwater, and glaciers will disappear. None of these consequences is given form in Fägerskiöld’s paintings.

Still, Fägerskiöld invests his works with historical and political meaning in more oblique ways. In Venice, Italy. View south. January 1 2100. (2022), he applies ultramarine along with black to conjure the deep, rich tint used by painters of the Venetian School, Titian in particular, a homage to the visual culture of a disappearing city. Kaliningrad, Russian Federation. View north. January 1, 2100. (2022) is shrouded in a rust-red patina, a depth achieved by slicks of lapidary color built one on top of the other. The painting appears to be enveloped in corrosive fog, according to Fägerskiöld a reference to pollution off Kaliningrad’s coast in the Baltic Sea, one of the world’s most contaminated bodies of water, due to oil spills, Soviet industrial waste, and German chemical weapons from World War II. These subtle tints also tug gently at skies fixed in memory—smoky and tinged yellow-gray after wildfire, crisp and bright after the first snow—reminding the viewer of the Anthropocene’s outsized influence on the natural world.

2100’s ambition toward cosmic boundlessness within canvas owes much to the sidereal paintings of Vija Celmins, who once remarked, “I like to think I wrestle a giant image into a very tiny area and make it stay there so that it seems inevitable that it is there.” At first glance, her Falling Star (2016) appears as accurate as a NASA photograph; evidence of her technique, which involves applying and sanding droplets of liquid rubber, is difficult to see on the surface of the painting. Fägerskiöld’s series, however, is always tethered to the materiality of oil painting, such that the viewer’s attention cannot disappear completely into the illusionism of the sky. Short brushstrokes seem to drift over layers of pigment, while stray pencil lines and flecks of paint on the border mark the artist’s hand. Slight disturbances on the surface interrupt the chronology of the stars to move back into the present, the pictorial space of the painting, varnished to such a high gloss that the viewer becomes an indistinct silhouette passing through the work’s dark reflection—shadowy, fleeting, and fragmentary, a vision of the Anthropocene from the perspective of the stars.