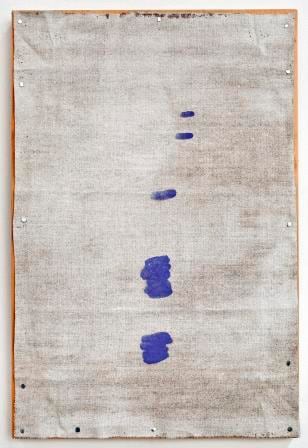

Icelandic Painting (12 Drops), 2012, watercolor on linen mounted on wood, 16 1/2 x 11 inches (41.9 x 27.9 cm)

Painter John Zurier stirs memories with color, light

By Rachel Howard

December 10, 2014

When John Zurier was a boy growing up with his father’s art collection, he used to watch the colors on the canvases change over the course of a day and “wonder what the paintings did at night.”

In his West Oakland studio, the pale light from high windows casting a calm glow on his work and on the white curls of his hair, Zurier still has a boyish playfulness in his brown eyes. You might not expect that mischievous energy from photo reproductions of the 34 works in his first-ever solo museum show, at the Berkeley Art Museum. The large, mostly monochrome paintings look flat when reduced to pixels, and the curatorial notes threaten a severe intellectual experience with their talk about Zurier’s absorption in “the object quality of his paintings.”

But in his studio, as in the open second-floor gallery of BAM’s current building at Bancroft and College (which will close Dec. 21 as the museum moves to a new location), Zurier’s paintings come alive. They beckon the eye with faint marks. As your senses absorb the subtle colors, and begin to trace the movement of the marks deeper into the linen’s weave, you might find yourself on the edge of a forgotten memory, or in a dreamlike state.

That’s what happened to Zurier, 58, when he saw his first Rothko painting in the flesh. “I was being very analytical, trying to figure out what Rothko actually did,” Zurier says. “And the next thing I knew I was overcome by a feeling which I hadn’t prepared for. And that’s what I’m interested in: the feeling that come after spending time with the work.”

Zurier was 20 when he saw that Rothko, after coming to UC Berkeley for a degree in landscape architecture. Though he grew up in Santa Monica and Beverly Hills, and his dad’s collection included works by such heavyweights as Joan Miró, Robert Motherwell and Richard Diebenkorn, Zurier wasn’t reared in the academic art world; his father sold copper tubing and his mother was a flight attendant. Zurier didn’t take a painting class until his junior year in college.

Then, in his first class with Joan Brown, Zurier knew painting was what he wanted to do. Soon another professor, Elmer Bischoff, became a mentor, guiding Zurier’s adventures in abstraction, though Zurier’s approach was to be entirely different from the New York Abstract Expressionists from whence Bischoff sprang.

“Elmer gave me this idea that you could find the color tone of the paintings – all the colors work together to create a very specific tone, and once that’s found, you could do almost anything,” Zurier says. “The color mood could develop, and then you could move into that space.”

He hand-mixes his pigments (his work table holds swatches of linen with a dozen watery blue dots), often combining them in animal glue to create a paint called distemper that BAM curator Apsara DiQuinzio says creates a “faint glimmer due to the rabbit skin gesso he uses.” The paintings in the Matrix 255 show range from barely-there whites with blue spots that recede like wave horizons on a lake, to glowing oranges and innocent turquoises. The method of creation matters less, Zurier says, than the complex reaction a viewer has to the colors.

“We register color as a thing, and then our memories associate with that color, and that causes a double feeling, registering the color first and then experiencing these subjective memories,” he says. “I want all these associations to come up. A memory on the verge – for me, that’s a pleasurable sensation.”

The play of light on San Francisco Bay was a major factor in his decision to settle permanently in Berkeley, where he worked as a preschool teacher and art supply cashier to support himself, finally becoming an adjunct professor for the California College of the Arts. But all the paintings in the Matrix show are inspired by Iceland. CCA asked Zurier to teach a summer painting class anywhere he wanted in 2011, and remembering a horseback riding trip he once took with his wife, Nina Zurier, a photographer, he chose the far-north country.

“It’s a very cold light there,” he says. “The effect is so subtle that there often isn’t a lot of strong contrast. And there’s a long extended twilight that lasts till 1:30 in the morning. I like the challenge of, ‘How can I re- create this light, which is so low contrast?’” He now stays in Iceland for three months every summer.

Still, though the light may be the visual manifestation, the experience of the painting, for Zurier as for the viewer, is a private reverie. For example, a painting titled “Finnbogi” – pale gray with a diagonal of robin’s egg blue in the top left corner, began as just a color Zurier felt drawn to – until, deep into the work on that painting, Zurier recalled an earlier painting he had made inspired by a building of that color in Iceland, which had since been torn down.

“So it ended up being a memory of a painting of a memory that no longer existed,” he says. No doubt that painting, like the paintings Zurier grew up with, does wily, elusive things in the night.