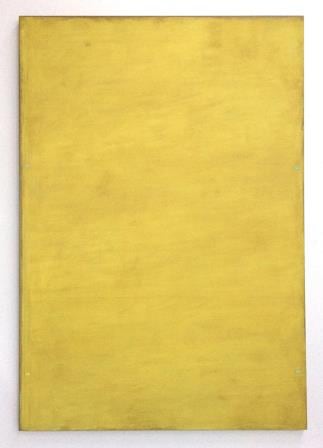

Sóley, 2015, distemper and oil on linen, 84 x 58 inches (213.4 x 147.3 cm)

New New Mexico exhibit to feature modernism, abstract paintings

By Jackie Jadrnak

October 21, 2016

Two new exhibits opening Oct. 28 at the New Mexico Museum of Art will give a roadmap from modernism to pure abstraction via detours through the Land of Enchantment.

The theme had its roots a year or so ago when curator Merry Scully was working on putting together a show of contemporary art. “We thought it would be nice to pair it with some historic works,” she said.

And all works are from the museum’s collection, some of them newly acquired and not seen in previous exhibits.

The journey in “Early 20th Century to Post-War American Art” will begin with Robert Henri’s “Portrait of Dieguito Roybal, San Ildenfonso Pueblo,” 1916, which shows the subject sitting with a drum between his legs, facing the viewer while beating a rhythm that almost can be felt in some glowing colors pulsating from the surroundings onto the drum itself.

It’s an appropriate start, Scully observed, since Henri encouraged other artists to come to Santa Fe, and worked with archaeologist and founder Edgar Lee Hewett in establishing the museum itself.

Henri is one of the founders of the Ashcan School, an arts movement that turned to the grit of urban life for its themes. His student, John Sloan, is represented by paintings showing women under the portal on the Plaza and another with people gathering at night to hear music on the Plaza, as well as sunset over the mountains – not quite urban, but representing everyday life in Santa Fe.

Two painters who came to New Mexico at Henri’s urging, Stuart Davis and Marsden Hartley, take viewers into the modernist aesthetic, with landscapes in a black-and-white palette, along with a color-drenched still life featuring a retablo hanging in a home.

Gene Kloss and Tom Lea’s works will show the influence of federal arts programs during the Depression, including Lea’s representation of a woodcutter and his burro, while other paintings will follow from the transcendental group, such as Emil Bisttram and Raymond Jonson, where subjects are rendered in increasingly abstract lines.

“They’re trying to use color and light energy almost in a spiritual way,” Scully said. “They hint at expansive ideas through abstraction.”

They’re joined by Agnes Pelton, Florence Miller Pierce and Stuart Walker, whose paintings are “very lyrical, very abstract,” Scully noted.

From there, the exhibit takes you through the hard-line, emotionally cool abstractions by artists such as Frederick Hammersley and John D. McLaughlin to the softer bars of pastel shades by Agnes Martin and the more emotive, swirling dark shades of Elaine de Koonig.

This journey sets you up for “Be With Me: a Small Exhibition of Large Paintings” in the adjoining gallery.

These large works include the colorful, chaotic geometrics of artist Nick Aguayo; the roughly textured monotones of Harmony Hammond, some painted on canvas once used in mats at a martial arts studio, and studded with belts and grommets; and the light, monocolor strokes of John Zurier.

In Zurier’s works, Scully explained, “you often see the canvas through the paints. He uses color and pigment purposely, but in a dilute way… . His work lies on the surface of the canvas.”

Hammond’s work, in contrast, “is very thick, impastoed … very body-like.”

The larger works in this exhibit, and its title itself, invite viewers to spend some time with each work, absorbing it as a whole and also giving time to notice the subtle details, such as the texture created in Aguayo’s works from marble dust incorporated into the paint, or a slight sparkle that can be detected in Zurier’s pigments.

“I hope people let it happen,” Scully said of allowing the paintings to soak into their consciousness. “For me, it’s a joy.”