"Sonja Sekula's Peculiar Architectures"

June 2, 2022

By Kito Nedo

In November 1947, after moving into a small apartment at 326 Monroe Street in Manhattan, close to the Williamsburg Bridge, Swiss-American artist Sonja Sekula penned a letter to her mother. ‘As I write to you looking out of my window,’ she is quoted as saying in Dieter Schwarz’s Sonja Sekula 1918–1963 (1996), ‘I think of all the contemporary American poets and artists who represent their outlook on this strange country, and I find myself beginning to realize that I shall be one of them.’ The move put Sekula at the heart of the New York avant-garde, where she already had contacts within the surrealist circle around André Breton and Max Ernst, and with abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell, while her new neighbours included the composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham. The 1940s and ’50s were to be the most productive period in the artist’s short life. In the mid-1950s, mental health problems forced her to return to her native Switzerland, from where she had emigrated with her family in 1936. She took her own life in Zurich in 1963.

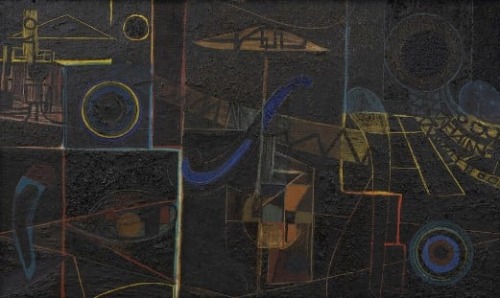

Most of the works in this compact exhibition date from the late 1940s and illustrate Sekula’s love of experimentation. In the mid-format Private Totem (1947), a dizzying proliferation of lines both suggests the emergence of figurative forms and contributes to their dissolution, while patches of white between the lines create a sense of animated three-dimensionality. Today, the painting illustrates the oftentimes appropriative approaches of the avant-garde, specifically the widespread fascination with totemism, which Sekula shared with many contemporary artists at the time: an early solo choreography by Cunningham (for whom Sekula once designed costumes) was titled Totem Ancestor (1942) and accompanied by an eponymous composition for solo piano by Cage. Nightpainting at Dawn (1946), on the other hand, seems to be inspired by urban nightlife: using a scratching technique, layers of colour are revealed beneath a black surface, joining to form peculiar architectures. By contrast, a small-format gouache, Untitled (1947), might be a view of the sky, with a wash-like layer of enigmatic symbols in white appearing to float above an azure ground.

Rather than a recognizable style, the thread running through Sekula’s oeuvre is her multidimensional and multilingual approach to her inner world and the society around her. Several works in the exhibition are situated in the transitional zone between language and sign, such as an untitled ink and gouache drawing from 1945, a pencil and gouache drawing on paper without a title from 1947, or the painting Earthman from the same year. She transformed elusive dissonances into images. ‘I consciously work in different directions,’ she wrote in 1957 as part of a schematic text drawing. ‘My tendency is the simple-multiple.’

Recently, major exhibitions such as ‘The Milk of Dreams’, currently on view at the 59th Venice Biennale, and ‘Surrealism beyond Borders’, currently at Tate Modern in London, have successfully sought to expand the surrealist movement’s overwhelmingly male and Eurocentric perspective. As a hinge figure between surrealism, abstract expressionism and the emerging fluxus movement, Sekula can be seen as playing a pivotal role in this context. Yes, despite various institutional appraisals over the years – a large-scale retrospective in 1996 between the Kunstmuseum Winterthur and New York’s Swiss Institute, for instance, as well as the inclusion of her painting The Town of the Poor (1951) in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York – her work has not yet found its rightful place in transatlantic art history, lending added significance and relevance to this enigmatic exhibition of Sekula’s work in Basel.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell

‘Sonja Sekula’, is on view at Galerie Knoell and Galerie Mueller, Basel, until 2 July 2022.