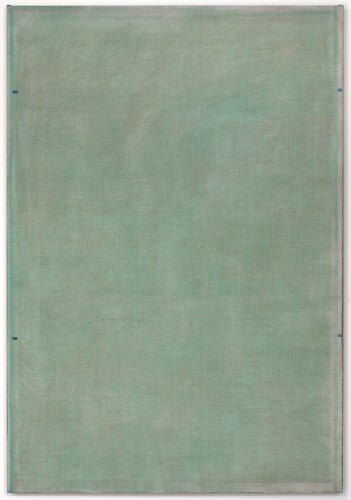

Late Afternoon in Three Parts (Elsewhere), 2017, glue-size tempera on linen, 84 x 58 inches (213.4 x 147.3 cm)

Ambiguity as Strength: A Conversation with John Zurier

By Jason Stopa

April 5, 2018

John Zurier is a painter who lives and works in Berkeley and Iceland. His work has been exhibited widely in solo exhibitions, most recently at Peter Blum Gallery in New York and Anglim Gilbert Gallery in San Francisco. This fall his work will be shown at Berg Contemporary in Reykjavík and Galerie Nordenhake in Berlin. Working in a reductive, monochromatic format, Zurier makes paintings in varying sizes that defy easy categorization. They aren’t provisional paintings. There is also no irony in them. Zurier’s paintings treat paint as both atmospheric light and as physical material on a surface. In “Slow Painting,” an essay recently published in A.i.A., Stephen Westfall describes the liminal quality of Zurier’s compositions: “Here and there a rectangle, a wedge shape, or a line may hold a composition, but these elements are the most refined of architectural members, meant to hold the veil or trembling membrane of color that is each painting’s keynote.” In his paintings, ambiguity is strength. In this interview, Zurier discusses silence in painting, the atmosphere of the San Marco convent in Florence, and chance operations, among other things that shape his practice.

JASON STOPA Your paintings have always possessed a sensitivity to temperature and touch. In your 2017 show at Peter Blum Gallery in New York, the color in your paintings was richer and beefier than it had been in previous shows. This density translated into a more complex atmosphere, where mark-making appeared more declarative and less recessive. What inspired the change?

JOHN ZURIER I’m happy you see it that way. I think it was a process of distillation. I can’t say what inspired it exactly. I was aware of wanting my paintings to be tougher and more resolute–especially since I am dealing with evanescence, with dematerialized densities of paint, color and light. All the paintings in that show were completed in a new studio. For thirty years I painted in studios with large skylights, where the light was really intense and coming from above and bouncing all over. In my new studio I have a long wall of floor-to-ceiling, north-facing windows. The light is still bright, but more diffuse, colder, and it comes from the side instead of the top. I can see the surface of the paintings better in the raking light. It’s just different.

STOPA Frederic Matys Thursz was a Moroccan-American painter of monochromes who scraped, glazed, and reworked his paintings to achieve a density of color. He once wrote “painting is invention, not reference or anecdote, neither depiction or alliteration.” His influence on monochromatic painting cannot be denied. At times your paintings capture a sense of a specific atmosphere, perhaps even a time of day. Do you make works that lend themselves a metaphorical or even poetic reading, or do you adhere to an austere approach like Thursz’s?

ZURIER I am fine with a metaphorical reading. But why not look for as open a reading as possible, or better, multiple readings? The paintings are wide open, physically and metaphorically exposed. My focus is on painting, and how the color, surface and brushwork all come together to make a certain light, not so much about making references. But they are there. I don’t deny them or try to remove them when I see them. I am looking for a light that is in the back of my mind. It’s something I have seen that defies articulation. It’s precise and it’s fragile, and I never know when it will appear. I am interested in the gap between abstraction and evocation, between what is determinate and indeterminate, direct and suggested. I hope the paintings can be seen as both austere and poetic.

The color for me is very specific. When I use malachite and lapis pigments mixed in glue-size and scraped into a coarse linen canvas, I can’t help but see them as inert substances but also simultaneously as the dusk of Iceland and the atmosphere in the cloister of San Marco in Florence.

Thursz’s paintings are terrific. Our work is chalk and cheese, and I am not so sure his attitude was as extreme as you say. I am very sympathetic to his feeling for Symbolist poetry and French postwar painting, especially the work of Jean Fautrier.

STOPA Fautrier is a personal favorite; he makes a painting like making a cake. There is a delicacy to the way he creates a surface, an incredibly light touch countered by a thick impasto and imbued references to the Holocaust. They are both sensual and ominous all at once. They are evocative paintings. There appears to be a growing group of painters that share common ground with what was once referred to as Radical Painting, which includes Marcia Hafif, Joseph Marioni, and Olivier Mosset. Their work, which is reductive and sparse, represents a few branches on the tree of monochromatic painting after Ryman. Their work inspired another generation concerned with similar aims but to a different effect, a generation that grew out of the postmodern ’80s: Michael Brennan, Daniel Levine, perhaps even the playful, tongue-in-cheeky monochromes of Jim Lee. Do you feel this kind of work is having a bit of a resurgence? Do you see yourself as part of a loosely knit group?

ZURIER I can’t answer your question about a revival of monochrome painting because I don’t think along those lines. The painters you named are good artists, but I don’t see myself belonging to a group. My friendships are pretty broad aesthetically, and we need friends to tell us what we’ve done and what we’re doing. Icelandic Conceptual artist Sigurdur Gudmundsson once said to me, “Artists don’t have colleagues. They have friends.”

STOPA In an essay for the February issue of A.i.A., Stephen Westfall writes: “Slow Painting is not anti-gestural, but Slow Painters for the most part avoid flourishes, emulating a relatively anonymous sense of touch.” I see your paintings as being about both a touch that anyone could have and a touch that only you possess. The balance seems to ebb and flow in your paintings. How do you approach intention versus chance? Do you see your approach to painting as antithetical to the ego driven work of painters today? Is it reactionary?

ZURIER Ebb and flow is a nice way of describing it. I would say that, intentional or unintentional, the touch is still mine, in the way that Marcel Duchamp explained it when he told Calvin Tomkins that his chance is his and someone else’s chance is their own. Chance helps to bypass the rational mind but not to escape the self. In terms of brushwork, Matisse and Munch are my primary models. My touch and its removal are in the service of bringing light to the surface.

No, my approach is not reactionary. I make the paintings I do because it is what I want to see and the experience I want to have. When I am painting, I follow the brush and my inclinations. Sometimes I feel my paintings counter the world’s cacophony, but that is more of an afterthought. Still, I would be OK with a response like that. In my studio, I have a photograph of Fra Angelico’s lunette fresco of St. Peter Martyr in San Marco’s courtyard, with his finger to his lips asking for silence. It reminds me that silence is both a spiritual principle and the condition of painting.

STOPA I don’t see your works as reactionary, but I do see them as unbothered by the many trends that painting cycles through in any given decade. I sense a desire to continue to explore a painting on an elemental level. They’re not as idyllic as some minimalist painters; they have a sober manner that has more to do with the world of appearances. You mention specific places where light has left an impact on your work–Iceland or Florence–and the influence of a fourteenth-century painter like Fra Angelico. Are these paintings in some way about essences, or notions of belief?

ZURIER In some respects, yes. I condense things and usually try to leave only what is necessary, but I am not a formalist. As others have said, attempts at reducing painting down to one essential thing—be it flatness, illusion or anti-illusion, or color—tend to fall flat in front of the paintings themselves. Looking for in-between states, suspension, a hovering in the air, variable qualities of light, I feel my paintings are more about ambiguity and openness than essences.