Fierce, Not Afraid. Indigenous Photography Takes the Spotlight

Chadd Scott

December 13, 2022

One of the first lies Americans are told about the country’s Indigenous people is that they were afraid of cameras, fearful the photographs would steal their soul. You’ve surely heard this. Somewhere.

You can’t remember exactly where, but you’ve heard it and were young when you did, too young to interrogate the truth of the statement. You simply took it as fact because you heard it from a teacher or parent or textbook or television–some authority figure.

Americans are served countless other lies about Natives through childhood in school and the media, but this particular lie–so simple, so memorable–likely formed much of what you believed about indigeneity: primitive, hopelessly trapped in the past, fixated on the supernatural, incompatible with the modern world, luddites.

Sympathetic, perhaps, but a lost cause. How can people afraid of cameras possibly thrive today?

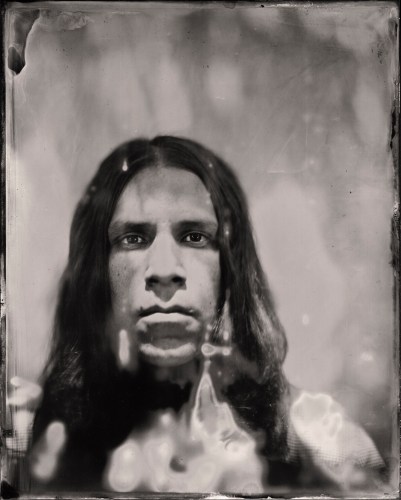

“Speaking with Light: Contemporary Indigenous Photography” at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Ft. Worth, TX takes on the history of how photography was used on Native Americans and how its increasingly being used by Native Americans. It stands as one of the first major museum surveys exploring the practices of Indigenous photographers working today.

“The mythic assertion that Indians fear our souls being stolen by the camera is a racist oversimplification,” exhibition co-curator Will Wilson (Diné) writes in the forward for the “Speaking with Light” catalogue. Wilson is also an artist with work in the show.

“There’s this long tradition of storytelling and the importance of representation and when this new tool comes into play, (Native) people aren’t scared of it because it’s some weird magic thing that’s going to steal your soul, they have a deep understanding of the power of representation and are weary of it because of that,” Wilson told Forbes.com.

Again from the forward: “Indigenous people have long expressed a legitimate criticism of the camera, a powerful technology with the capacity to discursively impose settler order through its lens.”

If your image was being used as a tool by an invading population to commit genocide against you, wouldn’t you similarly be “afraid” of the camera?

Wilson continues in the forward: “Since their migration to these shores, non-Native photographers have used photography to perform a representational deception by categorizing Indigenous Americans as others within our own homelands, or by representing Indigenous lands as terra nullius—unclaimed territory ripe for occupation. Through violent visual regimes, our image was processed, reoriented, and transformed into a spectacle of external difference and foreignness.”

Considered through the perspective of the subject, not the shooter, “Is it any wonder that Indigenous people were immediately suspicious of photography?”

No, it’s not, in response to a rhetorical question from Wilson.

The consideration of anyone’s viewpoint other than their own, however, has never been a strong suit of colonizers.

Photography’s power in shaping perception combined with its history of being used to subdue Native people makes for a testy relationship between the medium and Indigenous practitioners.

“Many contemporary Indigenous photographers share a certain ambivalence for the photographic medium,” Wilson explains in the catalogue. “On one hand, photography is a potent tool for self-description and determination that aligns with the remarkable capacity of Indigenous artists to illuminate their worlds through story. On the other, photography has been used to define, dehumanize, and regulate Indigenous peoples vis-à-vis our contentious relationship with settler culture.”

Wilson sees the images in “Speaking with Light” as, “a vibrant reclaiming of personal and communal representation,” matching his picture-making philosophy and “firm belief that representation has the power to transform worlds.”

Representation proves critical to understanding the exhibition and its artworks.

Who is being represented. How. And by whom.

“The artists actively decolonize photographic representation by articulating Indigenous representational subjectivity,” Wilson writes. “The exhibition acknowledges that Indigenous photographers have taken over the conversation about how our lives and cultures are represented.”

A conversation previously led for more than a century by America’s dominant white culture, Edward Curtis, Hollywood, none of whom were particularly interested in what was best for the Native people being photographed.

“Challenging the problematic histories of representation that bind us…the artists seek to empower their photographic subjects, representing them in manners that ensure they are participating in the re-inscription of their customs and values, leading to a more equitable distribution of power and influence,” Wilson writes.

Photographers working with their subjects, not merely using them. Indigenous photographers depicting Indigenous people as contemporary, valuable, possessing agency. In the hands of white picture makers, that was rarely the case. The result of those degraded representations being a degraded self-worth.

No longer.

“The power of being able to imagine yourself as a successful, important person and community member who’s working to benefit everybody and seeing that as a possibility,” Wilson told Forbes.com of the importance these images can have on Indigenous people.

Exhibited artists in “Speaking with Light” extend beyond Native America to include works by First Peoples artists living in what we today call Canada, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians.

“Speaking with Light” expresses what it means to live in contemporary Native North America through the lenses of young and mid-career artists such as Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke), Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit/Unanga), Cara Romero (Chemehuevi) and Sky Hopinka (Ho-Chunk Nation/Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians), as well as their generational forebears, including Shelley Niro (Member of the Six Nations Reserve, Turtle Clan, Bay of Quinte Mohawk), Tom Jones (Ho-Chunk), Zig Jackson (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara) and the late Shan Goshorn (Eastern Band Cherokee).

Artists whose cultural backgrounds would have at one time largely excluded them from museum representation in America are now being featured in exhibitions and permanent collections around the country. From Orlando to Salt Lake City, Columbus to Milwaukee, Native American photography is enjoying an institutional spotlight it has never previously. The Minneapolis Institute of Art will debut another major Indigenous photography exhibition even larger than the Carter’s in fall of 2023.

“There certainly is more attention being paid to artworks being created by Indigenous artists in all media, and for good reason,” exhibition co-curator and Senior Curator of Photographs at the Amon Carter Museum John Rohrbach told Forbes.com. “We have seen over these last three decades a blossoming of vibrant, diverse, and challenging work being made by Indigenous artists across many cultures. ‘Speaking with Light’ recognizes this trend in photography.”

Alan Michelson’s (Mohawk member of Six Nations of the Grand River) video Mespat (2001), presented on the artist's 14-foot screen made of white turkey feathers, and a new large-scale photo weaving by Sarah Sense (Choctaw/Chitimacha) stand out. The Carter commissioned Sense’s artwork and has acquired most of what is on view in the show continuing its efforts to build a resource of contemporary Indigenous photography.

An artform that is fierce, not afraid.